Operational Continuity as a Value Preservation Strategy in Acquisitions

A deeply held assumption is rapid integration equals discipline and control. On the contrary premature structural and operational changes often erode the local advantage for which premium was paid.

Most acquisitions fail not because the target lacked quality, but because value was unintentionally destroyed after the deal closed. Premature structural and operational changes often erode the trust, execution strength, and local advantage that took years to build.

Rather than advocating delay or passivity, this piece examines a counterintuitive integration logic, one that prioritizes what must not change. It explores why much of what makes an acquisition valuable is invisible at deal time and highlights a disciplined sequencing error that even sophisticated acquirers repeatedly make. Especially in businesses that operate locally and are tightly embedded in the communities they serve.

The framework culminates in a phased approach that reframes integration not as optimization, but as protection.

If you are involved in acquisitions, integrations, or scaling through M&A, this perspective will likely force you to reconsider where value is truly preserved or quietly lost after the transaction.

First Principle: Preserve What Stakeholders Experience

A fundamental rule of acquiring a successful operating entity is to avoid changing anything that key stakeholders directly experience in the first 24 to 36 months.

This is not conservatism. It is value preservation.

What the Acquisition Premium Was Actually Paid For

The valuation assessment at the time of acquisition was based on customer trust, local execution excellence, cultural fit with its market and proven operating rhythm.

And not based on potential processes or future org charts or future compliance readiness.

Local Optimization Already Exists (And Is Invisible)

It must be acknowledged that in any running operation, local optimization already exists. Over the years, the team has entrenched effective workflows to solve city-specific problems by building:

· Informal but effective workflows

· Developed trust with all external and internal stake holders

· Service model aligned to local expectations.

Replacing this with “best practice” systems removes the very advantage that justified the acquisition.

Information Asymmetry

At the time of acquisition only financials are visible, trends are modelled and infrastructure is inspected for valuation purpose.

But tacit knowledge is invisible. Judgment heuristics are undocumented. Cultural shortcuts are unknown. And, by changing operations before understanding destroys value blindly.

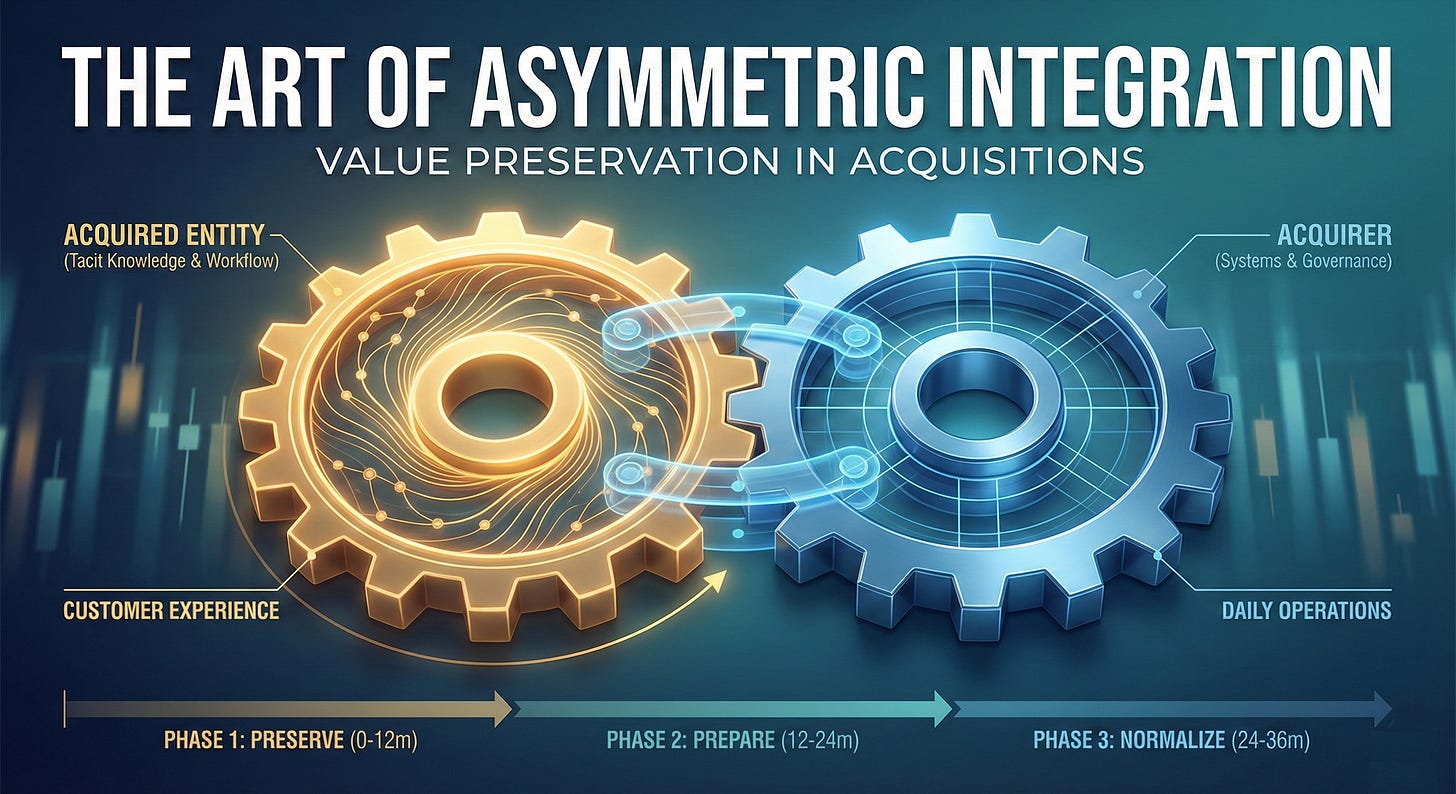

The Correct Strategy: Asymmetric Integration

In an asymmetric integration, control is introduced in areas invisible to customers and last in areas they directly experience.

Start with inward facing like

· Finance

· Governance

· Controls and risk.

Then work on outward-facing ones like

· Quality of Service

· Speed

· Consistency.

The mistake most acquirers make is reversing this order.

Distinguishing Critical from Cosmetic Change. Operational continuity does not mean ignoring genuine systemic risks. These represent risks to the acquisition itself and must be addressed immediately through corrective action while preserving the operational model where possible.

Everything else like efficiency improvements, organizational restructuring, process optimization and cultural alignment come gradually in phases.

Phase 1: Preserve (0 to 12 Months)

Objective: Do not break the trust.

Start by looking into areas which are invisible to customers, work in the back-end on areas causing no disruption such as financial consolidation, legal & compliance and governance reporting.

Make it amply clear to your auditors that they are not aligned to the current audit practices and will have to factor in the time required for assimilation.

Do not add new approval layers for procurement, payments, or front-office operations, nor burden them with excessive reporting. This can lead to daily friction causing trust disruption and being customer-facing will cause erosion of confidence as any change here immediately impacts perceived value.

This will ensure it runs exactly as before. A nominee retains decision authority while HQ observes and learns.

Phase 2: Prepare (12–24 months)

Objective: Build capability without forcing change.

Start by working on gaps identified in phase 1 and add staff capacity as required. Do not rush to remove perceived excess capacity, as the full operational picture is still emerging. Train teams on systems, introduce SOPs in shadow mode and build ops support.

Phase 3: Normalize (24–36 months)

Objective: Institutionalize without shock.

Start by gradually align processes. Introduce selective controls and transition authority smoothly.

The “Run Wild” Fallacy

There is a fallacy that delaying integration is equivalent to ‘letting them run wild’. Preserving operations is not abdication but respecting current execution methodology. Controls still exist via financial visibility, board oversight, capital approval and risk governance

This is trust with verification, not chaos.

Consequences of Premature Structural Imposition

Imposing structure too early leads to a predictable downward spiral: service quality drops, customer complaints rise, staff morale plummets, and attrition increases. Ultimately, the brand premium evaporates. And ironically, the acquired entity is blamed for underperformance, when actually it is the rush to change the operating model by the acquirer which caused it.

Conclusion: Integration as Value Preservation

For acquisition-led expansions, operational continuity is not a concession, it is a value preservation strategy. Entities acquired at a premium have already demonstrated local execution excellence, customer trust, and momentum. Forcing immediate structural or procedural change, especially in customer-facing operations destroys the very attributes that justified the acquisition. The correct approach is to allow them to operate as they have while gradually introducing back-end governance, systems, and capability building that do not disrupt daily operations. Integration must be inward-facing first and outward-facing last. Anything else accelerates brand erosion and undermines long-term returns.